M.F.A. alum John Hennessy is the Director of Undergraduate Creative Writing at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and poetry editor of The Common. He is also the author of two collections of poetry, Bridge and Tunnel and Coney Island Pilgrims, and co-translator, with Ostap Kin, of A New Orthography, a collection of selected poems by Serhiy Zhadan. In our recent update from him, he writes on the particular relevance of Zhadan’s writing in the present moment, his new experience of teaching in the age of COVID-19, and the way his M.F.A. professors’ mentorship of him continues to influence how he guides his own students.

Like most people around the world these days I’ve been physically, if not socially, distancing. Phone-calls, texts, WhatsApp messages, and Zoom meetings have kept me in close contact with my family, friends, students, and colleagues around the world, even as I pass my days in a condominium overlooking a cow-farm and sawmill right in the town of Amherst. (My “quarantine” set-up is complicated, involving two households, my sons, their mother, and their friends who were unable to return home when their college went to remote-learning.)

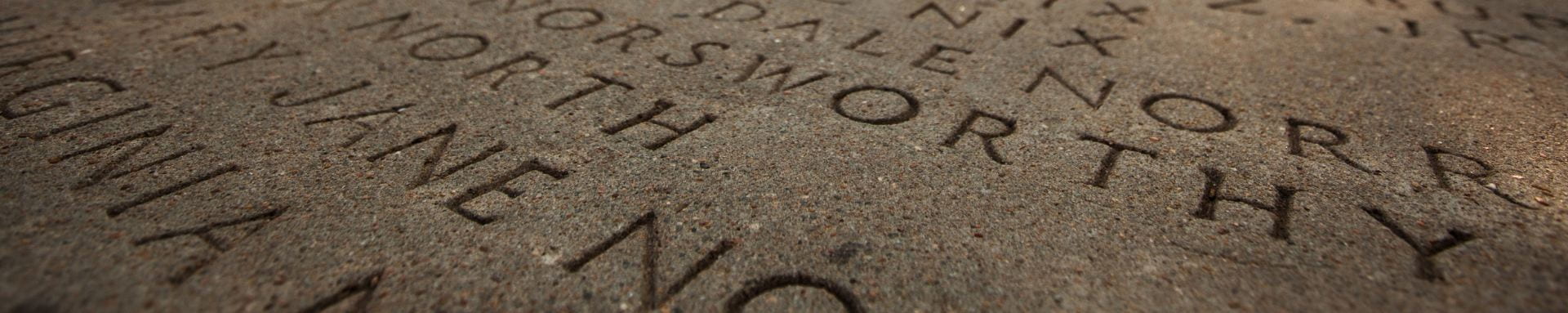

When not washing my hands—or wringing them—I’ve been working on getting the word out about A New Orthography, a book of poems by Serhiy Zhadan that Ostap Kin and I translated, published this spring, the fifth volume in Lost Horse Press’s Contemporary Ukrainian Poetry Series (University of Washington Press). Zhadan, one of Eastern Europe’s leading literary figures, is widely recognized as the voice of post-Soviet Ukraine, and these poems, many of them portraits of people adapting to uncertainty, danger, and anxiety, were all written since the start of the Russo-Ukrainian War (2014-present).

When the book arrived I read it again, this time as the United States began to effectively shut down, sheltering against the coronavirus. I was moved by how similar the experiences of the civilians, refugees, soldiers, and veterans Zhadan documents began to seem to life here. “You’ll get to wake up in a room/ listening carefully to your body,” Zhadan writes, noting that simultaneously peaceful and anxious moment in the morning as we reassess our physical state, check in with ourselves. There are empty or oddly-stocked stores, quiet streets (when the fighting stops), and essential services are taxed: a ruptured gas pipeline goes unattended because “no one wants to drive under shelling.” But there’s solace in these poems, too, as people forge connections, share food, news, and shelter, and finally attempt to “rebuild this world so it can be loved, / so you won’t feel this hopeless and ashamed in it…So much time left to save it all” (“Knights Templar”).

The first review of A New Orthography was published in March in The Kenyon Review, and Olena Jennings reaches a similar conclusion, that this is a book that has become especially relevant in these days of the coronavirus.

Meanwhile, those of us who can continue our work remotely are learning to do so on the fly. My classes at the University of Massachusetts are now meeting online, through Zoom. So far so good. Even in the virtual classroom I find myself sounding like my professors—in the way that parents might catch themselves sounding like their own parents: “Where’s the ‘contract’ with the reader?” “Is this ending earned?” “Can you dramatize that?” “Too much ‘walking across the floor’ in this scene.”

Everything I know about teaching creative writing I learned from my professors at the University of Arkansas, especially Skip Hays, Bill Harrison, and Michael Heffernan. There’s not a class that goes by that my students don’t benefit from their rigorous influence. But I must admit, times have changed, and I never show them the tough love that some of our (beloved) professors regularly dispensed. For example, I remember Bill Harrison calling me into his office after he’d read my first story in his class. “Sit down,” he said, and before I could he followed with, “I don’t like your writing. I want to like your writing—I like you, you seem like a nice enough guy—but I don’t like your writing.” There was something in the way he spoke that actually made me laugh—not because he wasn’t serious, he was, and he was basically saying that everything was wrong with my work—but he made it clear that it pained him to say this, and the responsibility was mine.

Finally he said, “You’re too earnest. Your writing is too earnest.” Of course I was upset, offended, hurt. Bill was known to be blunt, harsh, in his criticism, and I’d heard the stories. I laughed, though, because I was astonished that the stories were true. And that he made it seem like the pain was his, that I had put him in a horrible position. Don’t shoot the messenger, buddy.

I left his office and soon after began the first story I published. Bill’s words are included in that story, about bike thieves in Amsterdam: the narrator’s mother tells him that he’s not charming, he’s not like his father. “You’re too earnest to be charming,” she says, and the narrator understands that it’s no compliment.

I wonder, though, if I’ve ever had such an immediate and profound effect on a student. I spare them the tough love, but I am firm with them once we’ve built up a mutual trust and respect. Firm when they’re ready. Maybe Bill did something similar. Maybe he knew I was ready.